|

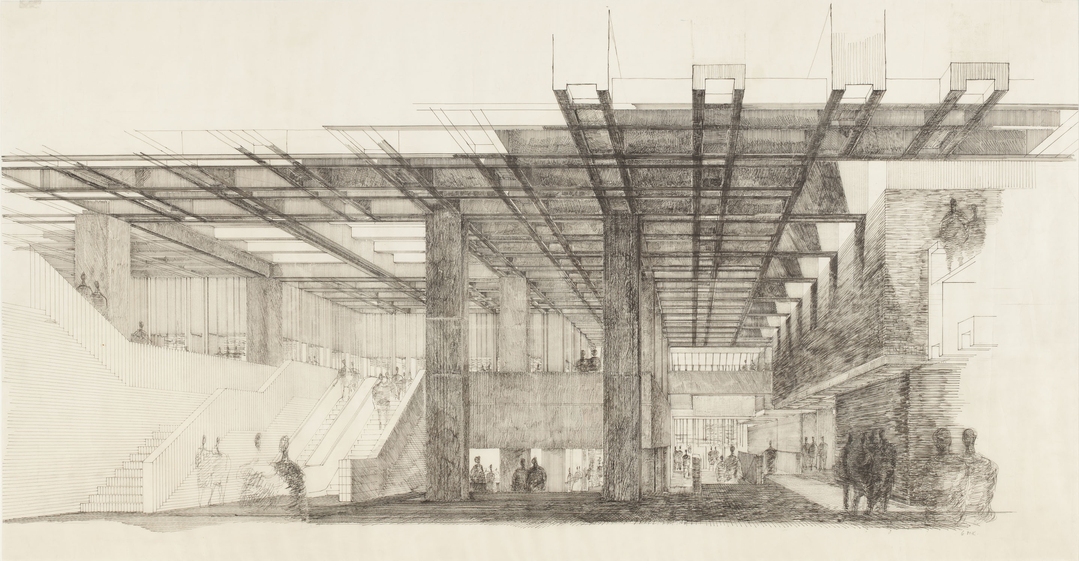

| Boston City Hall, Perspective Looking North, Second Floor North Hall, by Gerhard M Kallmann. Image courtesy of Historic New England. |

This October, the Huxtable fellows went to the Boston Society of Architects gallery space to see an exhibit of original drawings of Boston City Hall. It seemed serendipitous that we had the opportunity to see this collection, since on our very first meeting in September, in talking about our group's namesake, Ada Louise Huxtable, we had discussed her praise of the Boston City Hall design. Huxtable was the architectural critic for the New York Times from 1963-1982, and her writing style is marked by her sharp wit and humor and her popular column had a powerful impact on public opinion. She championed the importance and relevance of architecture to the every-day person. Many of her most famous pieces of writing were take-down pieces, wherein she eviscerates the unfortunate architects whose designs did not meet her standards. She insisted that we care as much about bad architecture as we do about the good, because the built environment far too important to be left either to chance, fashion, or a false perception of irrelevance.

Boston City Hall, even today, is a much reviled building. It frequently appears in online lists of the ugliest buildings of the world. Ask anyone in Boston, they either love it, or they hate it.

Ada Louise Huxtable flat-out loved it. She praised the Brutalist icon calling it "one of the handsomest buildings around, and thus far, one of the least understood." She proclaimed, "Boston can celebrate with the knowledge that it has produced a superior public building in an age that values cheapness over quality as a form of public virtue."

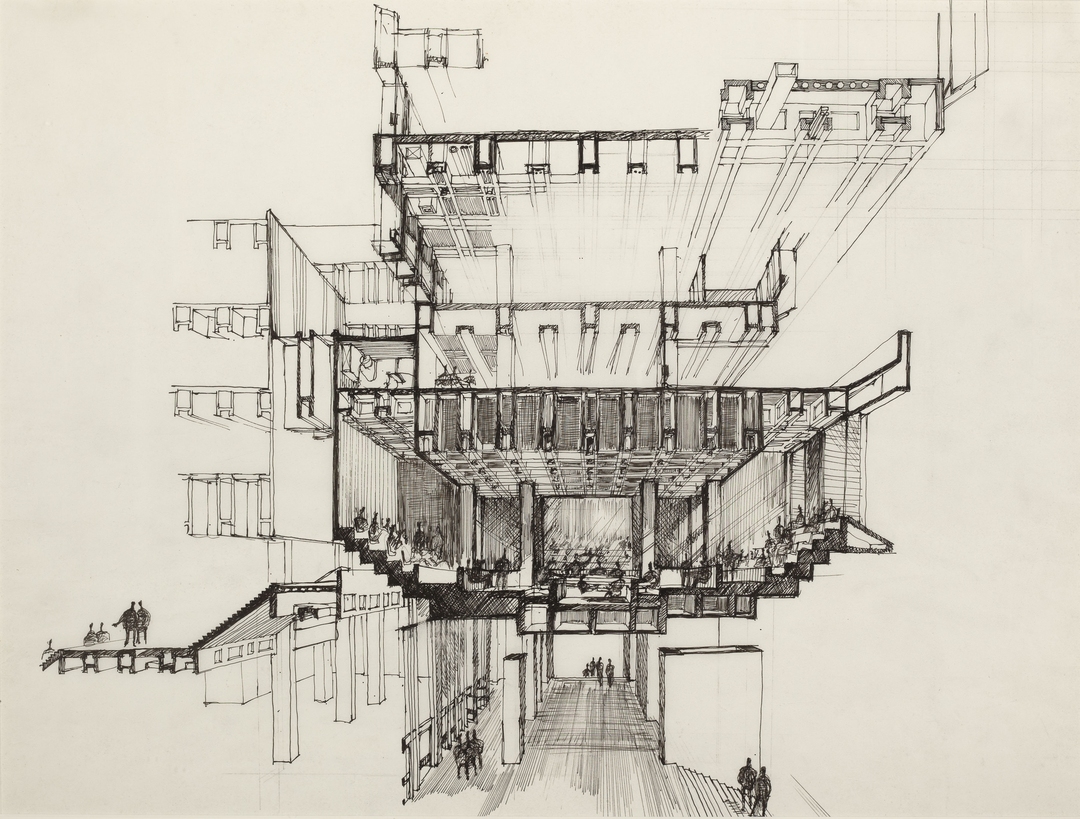

What she admired most in the buildings design was its magnificent monumentality, its radical difference from Boston's traditional architectural conservatism, but also importantly the attention paid to the experience of the visitor. This latter quality was startlingly revealed in seeing these original drawings. In viewing the drawings you can see how in the original design the ground floor of the building was entirely open, bringing the plaza into the building and allowing the free passage of Bostonians through the building towards Fanieul Hall. Inside, views of the city: the waterfront, Fanieul Hall, and Quincy Market, are framed by protruding deep concrete modular windows -- a design feature whose conception is evident even in the earliest sketches of the project. As visitors stood in the center of the space, great voids within the interior would allow them to see up into the various departments, allowing for a literal transparency into the workings of a city government infamous for its corruption and back room dealings. I was struck by how markedly different this vision was from the current experience of the building is -- nowadays if you wanted to make your way into the center of the building you would have to move through not one but two security checkpoints, the ground floor is entirely enclosed -- the building obstructs the landscape rather than incorporating it. This building serves as evidence of what a different world we live in today than what must have been in the 1960s, where radical openness and transparency could be made part of a major civic building. It's hard for me to imagine anything like it being built today.

|

| First Sketch – Site Section Looking North. Gerhard M. Kallmann and Michael McKinnell. |

To critique the critic and the exhibit further: Huxtable in her praise of the of the building, and the exhibition in its pristine presentation, both neglected to fully address the political context of the project. In the 1960s wide-sweeping efforts to revitalize downtown Boston led to the demolishing of entire neighborhoods where much of the working population and immigrants lived. These neighborhoods, including what is now the beloved North End of Boston (which luckily for us escaped the ravages of revitalization's bulldozers), where thought to be "slums": so decrepit, dirty and crowded that the only design solution for these neighborhoods was a clean slate. Below, you can see a picture of old Scollay Square in the 1950s from the same vantage point as the following image which shows Government plaza and City Hall just after construction. There is a sordid element to the project here, and a deep irony. For a project to claim to demonstrate ideals of transparency and accessibility in government, can it also be tacitly implicated in the destruction of a historic neighborhood? Certainly, we can say, times have changed.

|

| Scollay Square, before and after. |